A timely exhibition on the war for natural resources is running amid ongoing protests over a planned coal-fired power plant in Krabi

The work schedule was gruelling: he had three days to take portraits of 200 villagers. For photographer Roengrit Kongmuang, the task was compounded by the simple act of breathing.

“My nostrils became drier and I felt uncomfortable breathing in and out. I stayed there only two days and I already had a sore throat,” Roengrit recalls of his experience shooting at villages around Mae Moh coal mines and coal-fired power plants in Lampang province, sites of a long and bitter environmental dispute.

“Then I started to wonder how the villagers must have felt. What kind of life is it when you have no choice but to live next to a coal mine and coal-fired power plants? Do consumers in big cities know that in order to for them to have electricity, these villagers need to sacrifice so much?”

The toll of sacrifice stare out from the images. “Dark Side Of The City” is a photo exhibition that is on show at Bangkok Art & Cultural Centre until Sunday, a collaboration between two photographers, Roengrit and his brother Roegnchai, and Thai Climate Justice (TCJ), an NGO advocating clean and renewable energy consumption. At 1pm on Sunday, there will be the screening of the short film Civilai Mai Saard (Dirty Development ), which was shot around Mae Moh, followed by a discussion.

TCJ’s co-ordinator Faikham Harnnarong says that the exhibition, as well as the film, are timely events, especially with the ongoing protest against the planned coal-fired power plant in Krabi.

“The current government and Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Egat) have more coal-fired power plant projects in the pipeline, especially the one to be built on the coast of Krabi. We believe the Mae Moh case is a cautionary tale [about the irresponsibility of the authorities]. We hope society will get more information to make informed choices about what kind of energy sources and policies that Thailand needs to embrace,” says Faikham.

She adds that the exhibition seeks to emphasise the contentious proposal by Egat – a “myth” as some believe – that coal is clean and that we need to address the threat of energy security.

“My point is that we have alternative energy, renewable energy which is cleaner, less expensive and in line with the global need to respond to climate change by cutting down on fossil fuel emissions,” says Faikham.

Egat has explained that the coal technology is now clean. But to the activists, it is just “less dirty than it once was”. Faikham adds that our energy policy should seriously look at an option of clean renewable energy.

Roengrit and his brother Roengchai visited Mae Moh district in February to record the life of the people who lived in the smog of the plant. The villagers, Roengrit says, were co-operative, though he also sensed a note of hopelessness.

“I said to them, ‘Please look at the camera lens. I just want to tell the story of your life around the coal-fired power plants to Bangkok residents who consume electricity produced in your hometown’,” Roengrit recalls. “Some villagers laughed, and said many cameramen and reporters had taken their photos and wrote stories about their health problems. I felt speechless. All I could say was I would try my best.”

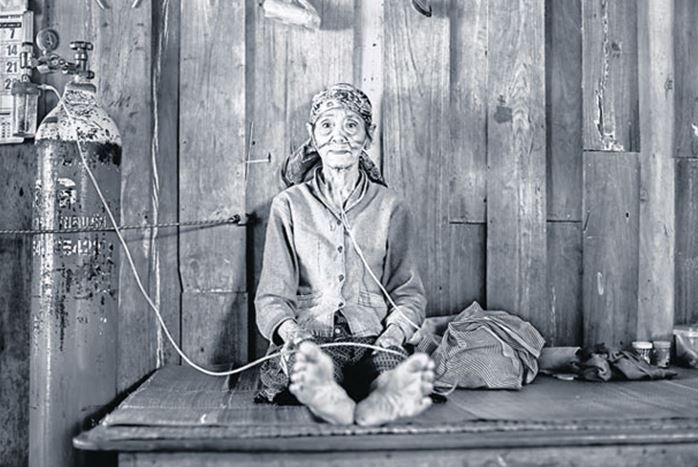

“Dark Side Of The City”, to some extent, delivers the photographers’ promise to their subjects. Eighty-four black-andwhite portraits showing the full faces of the villagers provoke powerful encounters between visitors and Mae Moh residents.

“I want city people to look into the eyes of villagers because there is something in them. The kind of eyes that can make you pause and have a closer look,” says Roengrit.

The case of Mae Moh coal-fired power plants is a reminder of how Thai authorities failed to uphold good environmental standards and provide remedies to those who suffered. The mining of Thailand’s largest lignite coal deposit began in the early 70s. Egat built three power plants in 1978, and more in the subsequent years. Problems started in 1992, when sulphuric content in the air exceeded the acceptable health standards by at least twofold. During the first two decades of their operation, the plants were not equipped with Flue-gas Desulfurisation (FGD), the technology used to remove sulphur dioxide from exhaust flue gases of fossil-fuel power plants.

Egat finally installed FGD in half of its 13 power plants in 1998. Now, every unit of every plant has FGD installed.

In 2003, 447 villagers sued Egat. Many plaintiffs subsequently dropped the charges. In February this year, the Supreme Administrative Court ordered Egat to pay compensation of around 25 million baht, plus interest, to around 130 plaintiffs. Each plaintiff will receive around 20,000-200,000 baht based on the severity of their illnesses.

“Dark Side Of The City” is the latest work by Roengrit and Roengchai that documents the environmental cost the rural people are forced to bear. In 2013, the two photographers were commissioned by National Health Commission Office of Thailand (NHCO) to take pictures of the environmental and health impacts at various mining sites, and the results have been compiled into a photobook Roy Mueng (Traces Of Mining Activities In Thailand ). The book was released last year, and copies were sent by the NHCO to public institutes and libraries free of charge.

Roy Muang contains images from 10 mining areas, such as Klity village near the former lead mine in Kanchanaburi province; the villages in Phichit around the gold mine operated by Akara Mining; the villages whose residents lived with an arsenic-contaminated water resource from a former tin mine in Ron Pibul district in Nakhon Si Thammarat. It also includes the iconic photo of a group of Dao Din students protesting against the guarding soldiers during the Yingluck Shinawatra administration at the controversial gold mine in Loei.

Roengrit says he just hopes that the images in “Dark Side Of The City” and Roy Muang will make people think about the hidden cause behind our rapid development. “You may agree or disagree with the debate about development projects and conservation. But I just wish society would acknowledge that these people exist. These photos confirm that the war over natural resources has already taken place and the catastrophe is huge.”

Story: Anchalee Kongrut

Source: Bangkok Post on July 24 2015

Photo source: National Health Commission Office